2.5 — Short Run Profit Maximization — Class Content

Contents

- Section 1: Wednesday, March 17, 2021

- Section 2: Thursday, March 26, 2021Section 2, because of no class on Thursday Feb 18 and Tuesday Mar 9, is 2 classes behind Section 1.

Overview

Today we briefly discuss revenues before we put them together to solve the firm’s profit maximization problem. We focus on the short run, where the firm incurs fixed costs and must stay in the market regardless. We derive the firm’s (inverse) supply curve.

Next class will be about the long run, and finish up unit 2.

Readings

- Ch. 8.1-8.3 in Goolsbee, Levitt, and Syverson, 2019

Slides

Practice

Today we will be working on practice problems. Answers will be posted later on that page.

Assignments

Appendix

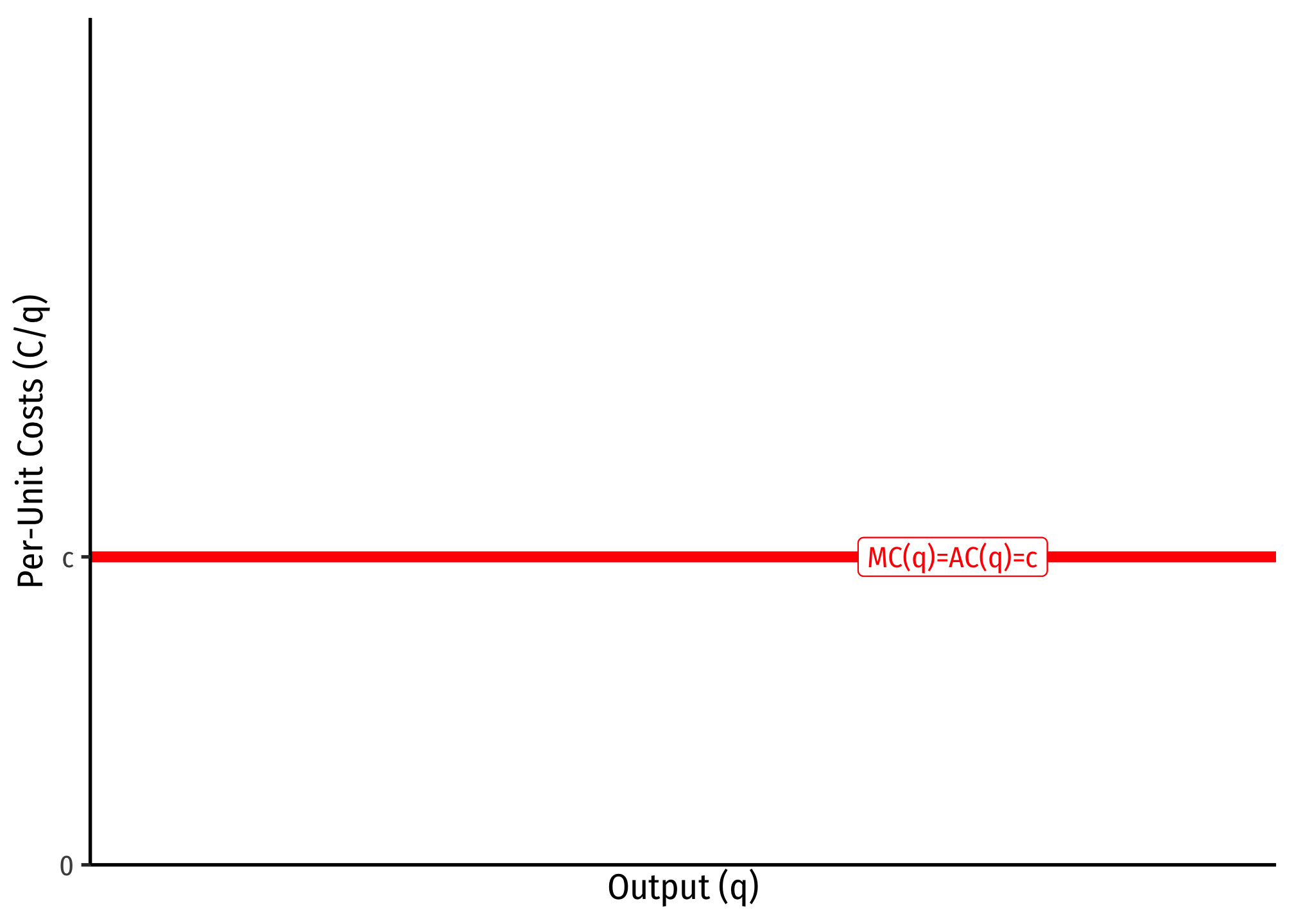

Common Cost Assumptions

Economists often make simple assumptions about costs to illustrate key concepts without marring the analysis with unnecessary complexity. This also makes graphs quite easy to point to and calculate key ares, such as profits or deadweight losses.

One common set of cost assumptions is the following:

- A firm has no fixed costs

- A firm has constant marginal costs, \(MC(q)=c\) where \(c\geq0\)

If this is the case, then we can show that average costs will be equal to marginal costs, i.e. \(MC=AC=AVC=c\).

Since marginal cost is the first derivative of the total cost function, integrating a marginal cost function \(MC=c\) leaves with with a total cost function of \(C(q)=cq\).Since we assumed there are no fixed costs, then there is no arbitrary constant from integration.

If this is the case, then we can find the average cost:

\[\begin{align*} C(q)&=cq\\ AC(q)=\frac{C(q)}{q}&=\frac{cq}{q}\\ AC(q)&=c\\ \end{align*}\]

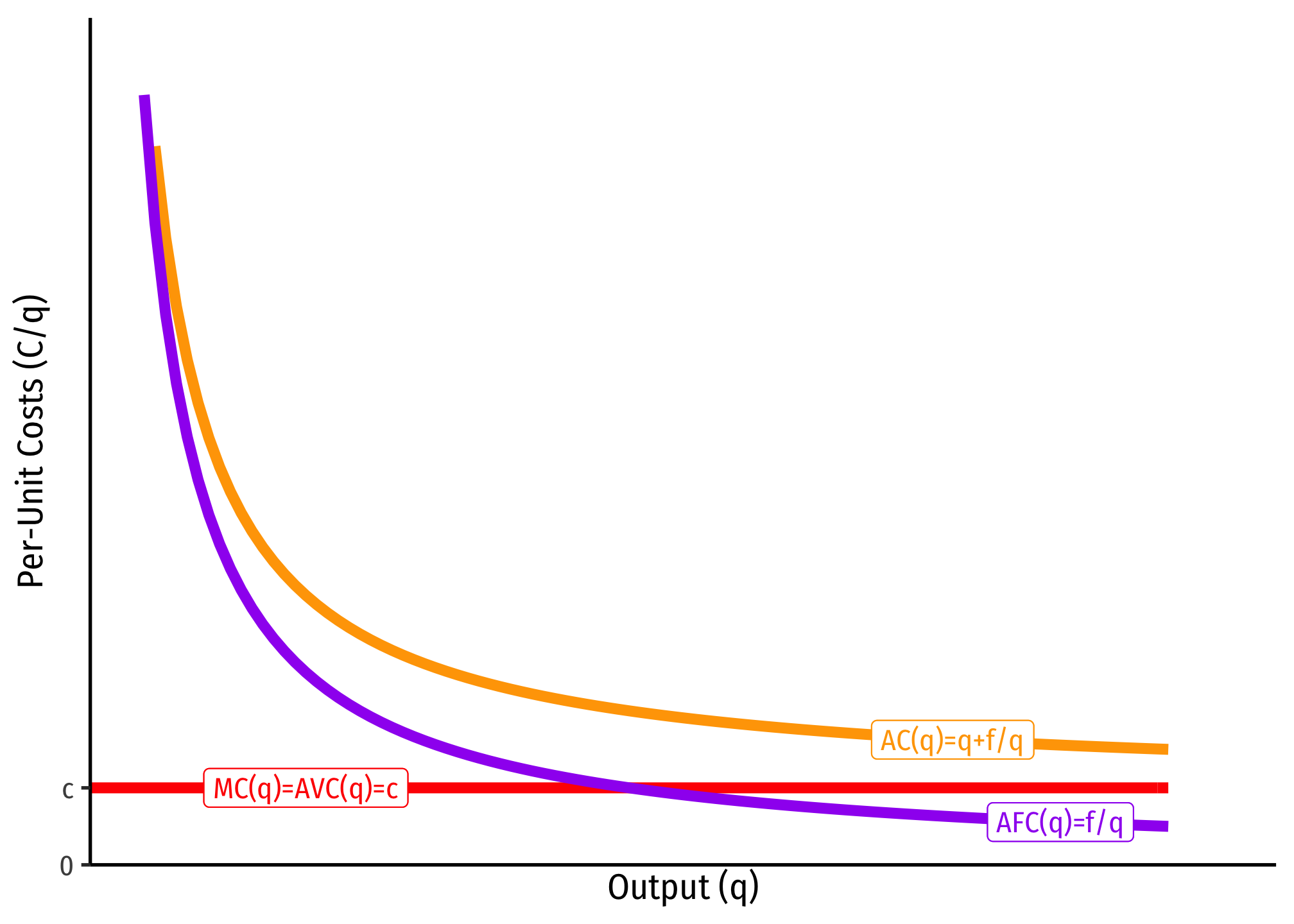

Another common set of cost assumptions is the following:

- A firm has fixed costs, \(f\)

- A firm has constant marginal costs, \(MC(q)=c\) where \(c\geq0\)

If this is the case, then we can show that average costs are strictly decreasing over all output \(q\geq0\).

Again, we can integrate marginal cost to the total cost function (but here we need the arbitrary constant from integration, which we shall label \(f\), for fixed costs): \(C(q)=cq+f\). We can then find the average cost:

\[\begin{align*} C(q)&=cq+f\\ AC(q)=\frac{C(q)}{q}&=\frac{cq+f}{q}\\ AC(q)&=c+\frac{f}{q}\\ \end{align*}\]

Since \(f>0\), as \(q \rightarrow \infty\), \(AC(q) \rightarrow c\), that is, average cost is getting asymptotically close to marginal cost, \(c\), but will never intersect it. Note, I also included AFC, which again is always decreasing, and asymptotically approaching 0.

The importance of this type of cost structure is that it creates economies of scale, and represents a lot of industries that tend towards natural monopoly.